by Jamie Havlin

1976 started with some sickening statistics in Scotland, January proving to be the country’s most murderous ever month on record, with seven killings in Glasgow alone and others in Barrhead, Dundee, Arbroath and Edinburgh. One particularly sickening murder had seen two children found gagged and battered to death in a tenement in Govan.

In the months that followed, other alarming statistics and stories emerged; including, after a spate of a dozen or so deaths, the growing menace of solvent abuse. According to the Glasgow Health Board there were a couple of thousand kids in the city sniffing glue. Stories circulated about terrified communities, particularly of old people afraid to go out at night due to the behaviour of feral gangs of kids, high on glue.

In rundown, litter strewn, side streets and underpasses, it had become not uncommon to see groups of nauseous looking young boys standing huddled together, some with sores round their lips and glazed eyes, as they blew and sucked glue fumes from emptied crisp bags, ballooning the plastic in and out, in and out.

Sniffers could quickly – and cheaply – achieve intoxication, initial euphoria often leading to disorientation before progressing to hallucinatory and delusional experiences of the sort that often gave rise to risk-taking or aggressive behaviour. Fits and unconsciousness were often common while under the influence, as was vomiting, which made asphyxia a possibility.

Strathclyde’s Chief Constable David McNee hit out at the increase in the figures and, that summer, the subject reached fever pitch, featuring in the pages of the Scottish press on an almost daily basis, Glasgow’s Evening Times positioning itself at the forefront of an anti-glue campaign along with the Scottish Daily Express and the Sunday Mail, whose front page headline, early in June announced the epidemic was now much worse than teenage alcoholism. In a bid to rehabilitate youngsters suffering from glue addictions, two centres were being set up to make advice and group therapy available, one in the small Ayrshire town of Stevenston, the other in Glasgow, where even kids in the 5-8 bracket, it was claimed, had tried getting high on solvents.

Around this time expensive import copies of a self titled debut album began making their way over from America to the more clued-up record stores like Listen in Glasgow and Bruce’s in Edinburgh.

The L.P cover presented a curious looking four-piece band. The singer looked like a basketball player who’d given up on eating or cutting his hair. He had a huge gash below the knee of his straight leg jeans, a leather bikers jacket several sizes too small, shades and white – or what might’ve once have been white – sneakers.

Together, The Ramones looked like a New York street gang and their songs like Beat on the Brat and Chain Saw stood apart from everything else being sold in Scotland at the time – or anywhere else on the planet for that matter.

Anyone hearing the album for the first time would, as the needle was guided onto the crackle of the opening grooves, be instantly struck by the almost impossibly high octane, relentless and pulverizing music; the simplicity of each song, the absence of solos and the choice of subject matter as Joey, in his unique, clipped delivery, sang in the oddest of accents about urban terrorists, rent boys and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. But it was the shortest track (at fractionally over a minute and half) that proved the most contentious.

Penned by bassist Dee Dee, the complete lyrics of Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue (punctuated with a 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8 chant) ran:

Now I wanna sniff some glue,

Now I wanna have something to do,

All the kids wanna sniff some glue,

All the kids want something to do.

The buzzsaw musical accompaniment being almost equally simplistic, though, for a few moments of variation, a guitar and bass riff served as a short instrumental break from Joey’s vocals.

Relatively few young Scots who weren’t avid readers of the music press at this point could claim to have even heard of The Ramones, though small pockets of enthusiasts did certainly exist north of the border.

Future Next Big Thing fanzine editor Lindsay Hutton, for example, had already purchased the album on a previous visit to the capital and was so enthralled by it that he made the long journey south from Grangemouth to attend their British live debut show on an unbearably hot and sweaty night on American Independence Day, 1976, the band sandwiched between The Stranglers and bill toppers, Flamin’ Groovies at London’s Roundhouse.

In Everett True in Hey Ho Let’s Go, he recounted why the night was especially memorable to him and his pal, ‘We met them at the side of the stage: they were thrilled that people from Scotland had come to see them, and gave us wee baseball bats’ (a Sire/Ramones promotional gimmick).

The concert, in front of by far the biggest crowd they’d yet performed to, was hailed back home as a major success in magazines like Rock Scene, who celebrated the show with a three page RAMONES BLITZ LONDON spread. Here critics were more divided, some even dumbfounded; Max Bell found them hilarious, ‘I reckon they’re closer to a comedy routine than a rock group,’ he wrote in his New Musical Express review.

Many agreed, including future Smith ‘Steve Morrissey’, who co-incidentally, would shortly become a contributor to Hutton’s fanzine. He fired off a letter to the music press, castigating The Ramones and stating that his beloved New York Dolls and Patti Smith were ‘the only acts which originated from the N.Y. club scene worthy of any praise,’ although did he later completely reverse this opinion.

After a headlining show the following night at Dingwalls, the group returned to NYC and their first British single Blitzkrieg Bop was released by Sire. They played a series of gigs on America’s East Coast, took a short break, and then embarked on a 13 date tour of California in August.

In the middle of that month, another glue related craze came to light in Scotland following another pointless death, the Sunday Mail devoting its front page (headlined The Life Extinguishers) to a 16 year old who, after having discharged a gas canister, had died as a result of inhaling the vapour, the fumes affecting his nervous system similarly to an anaesthetic given during an operation – but, of course, without having a skilled anaesthetist on standby to help in case of emergency.

Shortly afterwards, another boy died after sniffing gas drawn from cigarette lighter fuel in a notorious part of the East End of Glasgow nicknamed Nightmare Alley. Apparently local cops had warned him off before but they couldn’t do anything about it as sniffing butane wasn’t illegal.

One MP in particular began monitoring the worsening situation even more stringently. Born in 1917, James Dempsey had been MP in the constituency of Coatbridge and Airdrie since the late 50s. In the House of Commons in 1968, he’d called for a prohibition on selling certain commodities to persons under 18, after learning of the awful case of a 14 year old who’d died from the injuries he’d sustained after another boy – while buzzing on glue – had thrown a lit firework at his face.

Appalled that that particular incident had proved to be far from isolated, Dempsey continued trying to combat the menace of glue; the two towns he represented having high numbers of youngsters afflicted by the problem.

When the angry parent of one contacted him that summer, it set in motion punk rocks’ first ever newspaper front page, the concerned parent’s son having bought a copy of The Ramones’ album.

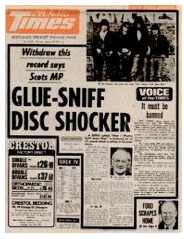

On the 19th of August, the Evening Times ran a ‘Special Report’ on the song Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue, accompanied by a large photo of the band and the front page headline:

Withdraw this Record says Scots MP

GLUE-SNIFF DISC SHOCKER1

Dempsey, who by no means fitted the category of out-of-touch publicity seeking politician, became even more determined to bitterly oppose anything that might possibly encourage more young people to put themselves at risk, which, he judged, included the removal of Ramones from record racks across the country.

The Evening Times editorial backed his stance to the hilt and called for the L.P to be banned, maintaining that pop fans were influenced by records and often attempted to copy their idols: ‘A record on glue-sniffing is bound to sow the seeds of the idea in the mind of impressionable youngsters.’

An expert in the field, Dr. Joyce Watson, agreed, admitting she was surprised any Americans would write such a song and pointing out the extent of the problem in that country, where several states had either forbidden the sale of glue to youngsters or made it an offence for shopkeepers to sell it to them.

Asked if Radio Clyde would be banning the record, station boss Andy Park was adamant they wouldn’t, albeit only because, ‘Banned records tend to become very popular’. Some DJs at the station made a point, though, of declaring they wouldn’t be giving it any airplay. Not that airplay on that particular station was remotely likely anyway.

Listen’s Steve McNaughton didn’t see a problem in continuing to stock the record in his Glasgow store and declared the paper was wasting his time by even asking about the song’s potential to encourage young people to try out glue and a spokesman for distributors Phonogram claimed to be unaware of the solvents problem in Scotland and, after consultation with the company’s management, confirmed there were no plans to voluntarily stop selling the LP, arguing that they didn’t want to be ‘self-appointed censors’ and that they had yet to be given any reliable evidence to confirm that the lyrics were an incitement to sniff glue.

Had The Ramones ever been solvent abusers themselves?

Overwhelmingly the evidence suggests they had been.

Dee Dee later admitted that he would take anything to get high as a youngster, including glue, and – if desperate – cans of whipped cream from the nearest supermarket, which he would sniff the gas from. According to guitarist Johnny, at High School, girls wanted nothing to do with any of the band, leaving the boys with nothing to do except climb rooftops and abuse solvents.

Furthermore, a week before the Evening Times story broke, Charles Young, in Rolling Stone, had covered their personal use of glue in an article, The Ramones Are Punks and Will Beat You Up; drummer Tommy was said to have built model army tanks and got high from the glue given away with the kits. ‘A lot of our music comes out of that sensibility,’ he told Young. ‘We’re intellectual twelve-year-olds.’

Already the group were planning on a follow-up LP and had written a track titled Carbona Not Glue; Carbona being a brand of (sniffable) cleaning fluid, common at the time in the States – though the song was actually later removed from the album to avoid a potential lawsuit with Carbona.

The outcry in Glasgow rumbled on and, of course, McNaughton and Phonogram weren’t alone in speaking out against potential censorship.

Chalkie Davies and Phil McNeill covered the controversy for NME and even outlined a method they claimed was a lethal Gorbals speciality of ‘running mains gas through a bottle of milk then drinking the milk,’ while also contrasting the legality of solvent abuse with the far less dangerous, though outlawed, use of marijuana.

Although both disagreed with much of what the MP had to say, they did recognise the his good intentions, Dempsey explaining that he welcomed the setting up of centralised clinics where those with solvent addictions could be diagnosed and helped rather than punished.

As the journalists rightly pointed out, Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue had been released long after the first glue fatalities in Scotland, so though the pair did sympathise with ‘panicking parents and paternal parliamentarians’, they believed that, ‘It’s obviously complete idiocy to go banning records whether they celebrate or denigrate glue sniffing.’

NME also contacted the band in Los Angeles to quiz them on the song and one (unnamed) Ramone responded by pointing out that they could write songs about people jumping off bridges – which wouldn’t imply that that’s what they thought people should do. The song was a joke and they wanted everybody to understand that. ‘We know the stuff is dangerous. You feel sick afterwards.’

Manager Danny Fields made a similar point, asking: ‘Why should the song be banned? War films aren’t banned on the grounds that they advocate violence.’

Depressingly, the craze continued with more deaths in Scotland and elsewhere; Dempsey continued his campaign to battle solvent abuse but the record remained available. Whatever anybody’s opinion on what John Holstrom, a co-founder of New York’s Punk magazine, later called ‘the first big punk scandal’ was, it would be hard to argue that the free publicity hadn’t alerted many to The Ramones and the new wave of music emerging from New York.

*

The controversy was reignited the following summer when The Ramones, together with Talking Heads, were scheduled to play in Glasgow’s Strathclyde University late in May and the New Yorkers again made front page news in the Evening Times, this time with a NEW PROVOST IN PUNK ROCK ROW headline, when the city’s latest Lord Provost, a pensioner called David Hodge, insisted he’d do everything in his power to keep the band away from the city.

The situation this time round was probably best summed up by Stephen Kelly, the Social Secretary of Strathclyde Uni’s Students Union, who pointed out on the Evening Times’ Talk of the Readers page that, ‘At Strathclyde the audience will be about 600 intelligent and educated people over the age of 18, all fully aware of the dangers of glue sniffing.’ Another letter writer echoed his point, complaining, ‘There is no room for this kind of pompous censorship in Glasgow’.

Up until the night of the concert, many suspected that a last minute ban would be enforced but in the end, the nearest threat to a cancellation occurred when the PA blew out during an afternoon soundcheck, necessitating a frantic search for a replacement which was eventually sorted, when they managed to borrow some gear from the nearby Glasgow Apollo, where Television, by coincidence, were headlining the following night on their first ever British appearance, supported by Blondie, the two shows being dubbed ‘The Weekend CBGBs came to Glasgow’.

The Ramones themselves would headline the Apollo before 1977 was out and this time round, although around 3,000 fans would be attending and the venue imposed no age restrictions, few murmurs of dissent were even voiced against the show.

1 Usually misquoted as ‘Ramones in Glue Sniff Death Shocker’ or ‘Outrage’.

Jamie Havlin

One Response to "Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue"